Sheila Estrada was pronounced dead at 6:15 am on Saturday January 18, 2025. Her body was found on the second-floor stairway of an apartment building in Hunts Point, a neighborhood in the Bronx. She came in as an unknown person and was identified through fingerprints. The cause of death was “acute intoxication combined cocaine and fentanyl.”

I met Sheila in 1996 when she was detained in the youth justice system in Massachusetts. I was a Professor at Boston College Law School, building a law clinic representing teenage girls involved with multiple systems. Our theory of change was that holistic representation could improve life outcomes by accessing education and mental health resources, reducing incarceration and increasing stability. Sheila’s case was a perfect fit for the model.

At 16, Sheila was well-known to Massachusetts child-serving systems. When Sheila was 4-years-old she was placed in foster care due to abuse and neglect by her mother. By the time she was committed to the delinquency system as a pregnant 16-year old, she had been in close to a dozen foster and group homes, been the subject of 15 reports of physical or sexual abuse and neglect by custodians, including a foster father, had “run away” from placements many times, and had been in multiple residential and mental health treatment centers. Over her childhood in state custody Sheila would have many different social workers. She was identified as in need of special education services but those services were inconsistent, she changed schools many times and never graduated. Over her teenage years Sheila was diagnosed with depression, PTSD and bipolar disorder and never received consistent treatment for her extensive childhood trauma. Sheila’s childhood experience in the systems was extreme, but it was not unique.

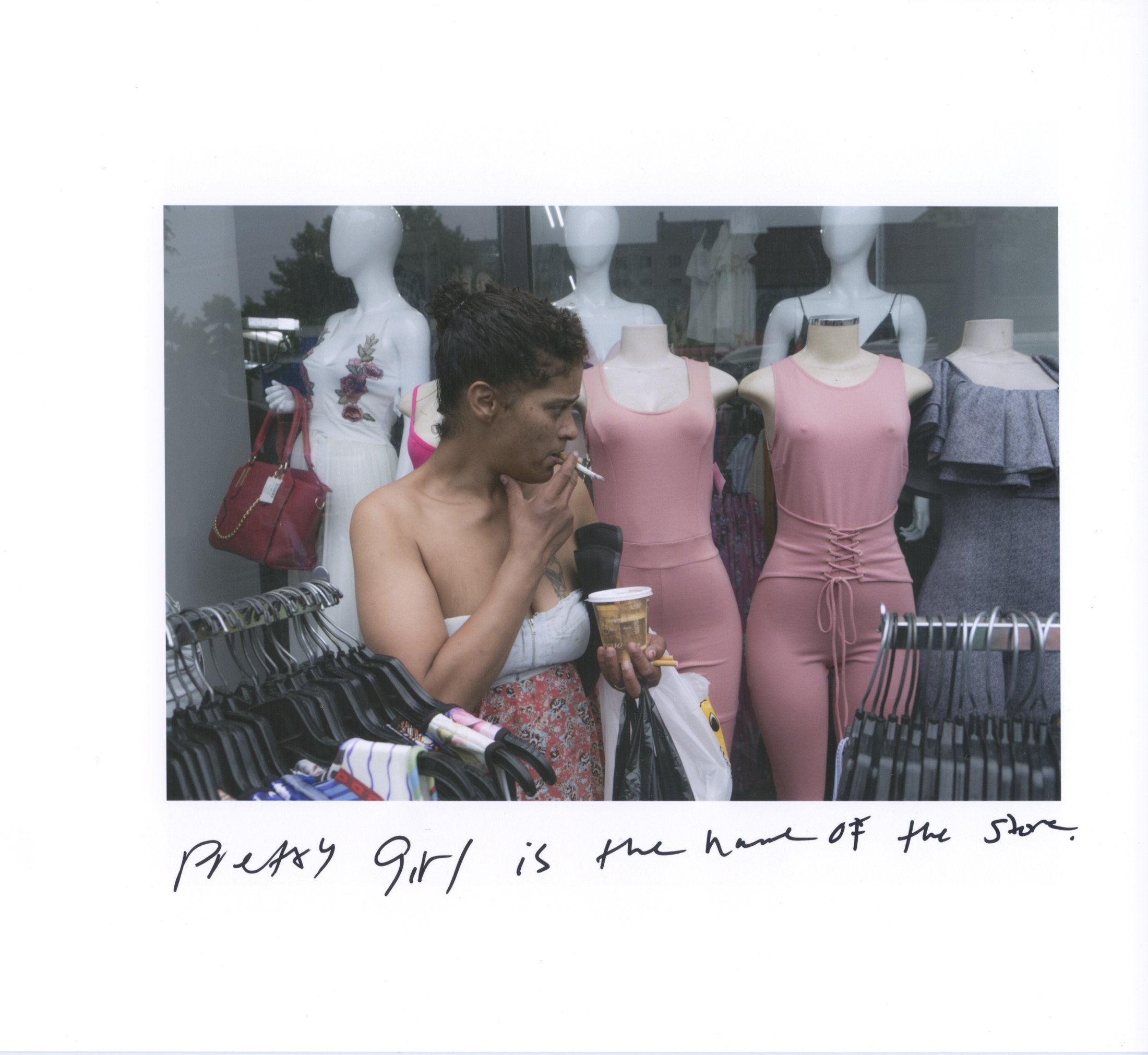

In 2013 Sheila was trafficked to Hunts Point in the Bronx, NY where she lived until her death in January 2025. Over her 12 years in Hunts Point, Sheila was mostly unhoused, moving around among friends and people who took advantage of and hurt her both physically and psychologically. She was known by her street name, “Anna.” She lived and supported her worsening addiction through survival sex work and built a community of women and others in situations like hers. Her Hunts Point world consisted of approximately 6 blocks.

Research tells us that Sheila’s adult struggles with addiction, exploitation, homelessness and the criminal justice system were inevitable by-products of her childhood in the foster care and youth justice systems. Sheila’s adult life was haunted by her feeling of being an outsider, without family or sustained relationships. “It’s the loneliness that gets me, the feeling that I don’t have anything or anyone.”

From 2011-2025 Sheila and I met periodically to spend time together and to document her experience in photographs and text. Sheila wanted her story to help students and others working with children in the systems. The Life and Death of Sheila Estrada, 1981-2025 (forthcoming) is a soft cover magazine format publication that juxtaposes Sheila’s inner struggles with the law and policy that failed her as a child—putting a face to the lifelong consequences of system failure.